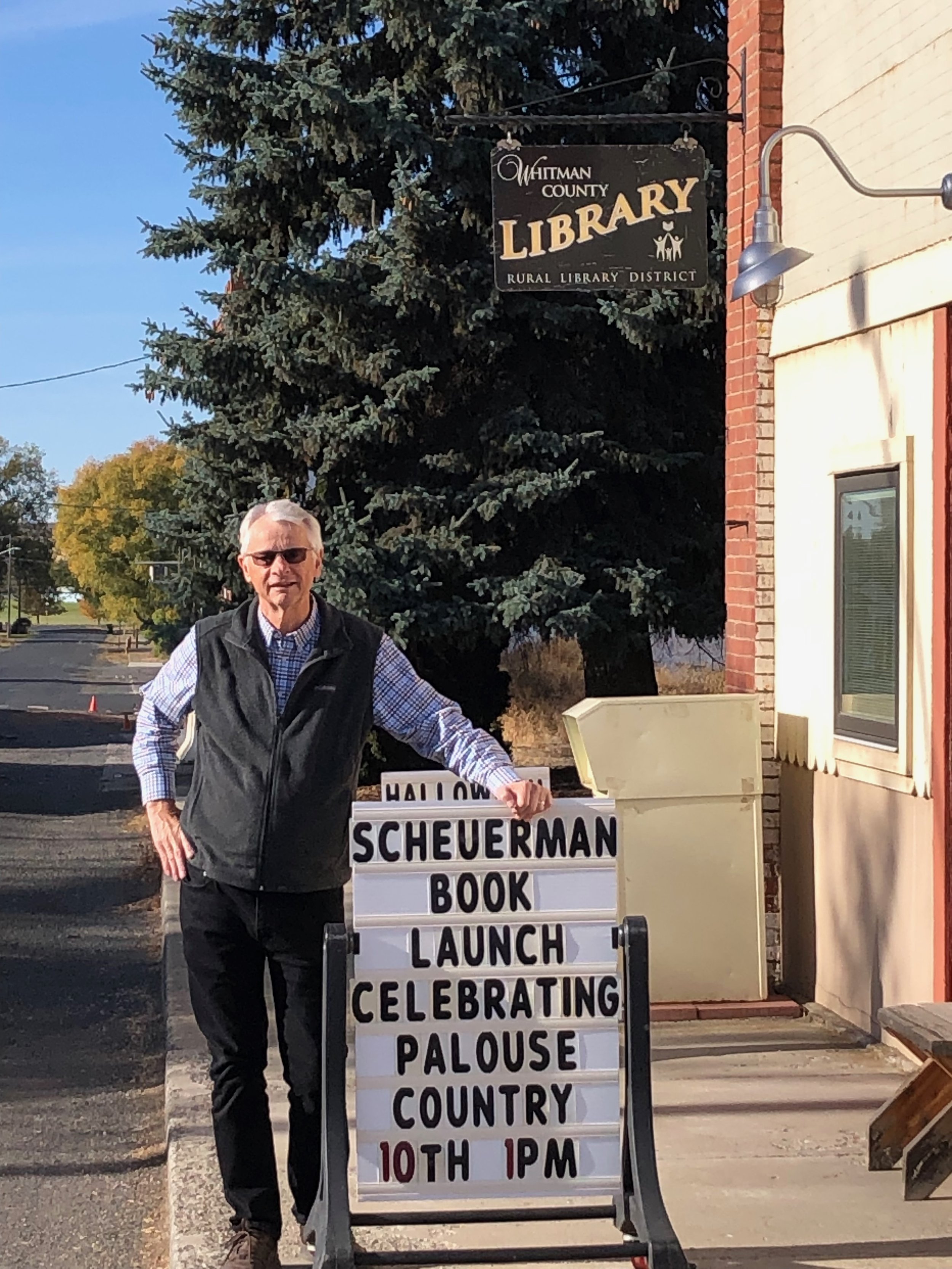

Interview with Dr. Richard Scheuerman; Richland, Washington

Bianca Hillier, The World; Broadcast June 20, 2022

The US is a major exporter of wheat around the world. But according to experts, most modern US wheat can be traced back to Turkey Red Wheat, which Mennonites brought from present-day Ukraine in the late 1800s. The World's Bianca Hillier reports.

NPR: Tell us a little about your background and where you live.

Richard Scheuerman: My wife, Lois, and I reside here in the Tri-Cities of Washington State which is located in a region of remarkable agricultural bounty known as the Columbia Plateau. We were raised in the rolling hills of Eastern Washington’s scenic Palouse Country where our family farm was located between the rural communities of Endicott and St. John. Among the earliest immigrants to the area were Germans from southwestern Russia who had settled in the Volga region under Empress Catherine the Great in the late 1700s, while others established farming colonies in the Ukraine’s Black Sea region in the early 1800s under Catherine’s grandson, Tsar Alexander I. My great-grandparents immigrated from Russia to Kansas in 1888 and continued on to the Palouse in 1891. They first resided in what our elders called the “Palouse Colony” which was a small agrarian commune along the Palouse River where today we operate Palouse Colony Farm.

We raise non-hybridized landrace “heritage” grains for artisan baking and craft brewing used at places like Ethos Bakery and Stone Mill in Richland and The Grain Shed in Spokane. We began the work of identifying and propagating “Palouse Heritage” varieties in 2014 with Stephen Jones, Steve Lyon, and Kevin Murphy of Washington State University and Alex McGregor of the McGregor Company, and established demonstration plots at our farm and at the Franklin County Museum in Pasco. The community of Connell in central Franklin County was first called “Palouse Junction” for its strategic location as an important Northern Pacific Railroad grain terminal. Numerous Germans from Russia and Ukraine settled in that vicinity as well, and the area figures prominently in author Zane Grey’s 1919 best-seller The Desert of Wheat in which Turkey Red might well be called a principal character.

NPR: How did you come to be interested in Russian and Ukrainian agriculture?

Richard: When you’re raised in rural communities many of your nearest neighbors and best friends are elders in their 80s and 90s! I came to enjoy visiting with first generation immigrants who told captivating stories about life in the Old Country—riding camels, encounters with the peaceful nomadic peoples of the steppes, raids by roving bandits, and the beauty and bounty of the native grasslands which their ancestors transformed into one of the world’s breadbaskets. I gathered many of their tales and later published them as books of history and short stories in works like Hardship to Homeland and Harvest Heritage.

In the wake of the Soviet Union’s collapse in the late 1980s, I traveled to Russia and Ukraine over a dozen times to assist in establishing a series of student and faculty exchanges between schools of higher education there and in the US. During those years I also visited the ancestral villages of my ancestors and arranged with various archives to duplicate about 10,000 pages of original source material related to various aspects of Volga German and Black Sea settlement. Having been raised on a farm where my elders shared many stories of Old Country rural traditions I had special interest in their accounts of farm life.

NPR: How have grains from southeastern Europe influenced American agriculture and culinary history?

Richard: Well it’s not much of an exaggeration to say that before pioneering Midwestern immigrant farmers started raising “Turkey Red” bread wheat in the 1870s that there was no bread such as we know it today made in America. Of course folks were baking breads since early colonial times, but it was made from soft white and red “Lammas” wheats from the British Isles and western Europe that is better suited to flatbreads, scones, biscuits, pancakes, and the like. Production of many of these varieties like White “Virginia May” Lammas, which we have worked to revive and was used to make Northwest Indian frybread, were devastated in the 1770s by Hessian fly infestations. So our early “Founding Farmer” families like Washington, Jefferson, John and Abigail Adams—Abigail supervised most of the farm work—and others devoted considerable attention to acquiring new grain varieties.

Among those they introduced by the 1790s was semihard Red Mediterranean, and Red Fife in the 1840s to Canada which was actually a bread grain from the western Ukraine district of Galicia. But it was not until German Mennonites from the Ukraine settled in central Kansas in the 1870s that one of their leaders, Bernard Warkentin, began raising Turkey Red. It was a hard red bread grain native to the Crimea, and its seeds began an agricultural and culinary revolution in the US in figurative and literal terms.

NPR: How was Turkey Red different from other grains raised in the US?

Richard: Turkey Red was America’s first true hard red bread wheat. That is, the kernels possess gluten proteins with a cross-hatch molecular structure that traps gases produced by yeast that makes bread dough rise. Not only that but the nutritionally dense inner endosperm and fiber make for an incredibly delicious loaf that has a naturally sweet, nutty flavor. Many farm families safeguarded their Turkey Red for personal use and sold other modern varieties they raised. Turkey Red was hard on early milling equipment, but once folks found out how wonderful the bread tasted they wanted more. And concurrent with production of Turkey Red was the advent of improved hammer-milling technology that produced a better quality of flour. Of the many modern varieties of bread grains raised throughout North America, virtually all can trace their lineage back to the Turkey Red native to Ukraine.

Americans tend to like their bread lighter in color than other places where people routinely dine on whole grain brown breads, and Americans tend to prefer clear brews when various styles throughout the world are cloudy. A premium is paid today for hybridized hard white bread wheats but in extremely rare cases Mother Nature does create a naturally occurring hard white wheat so you can have a high fiber, light colored loaf. Over a century ago a USDA grain explorer was traipsing across Persia—present Iraq, and found a grain vendor in a bazaar who was said to have wheat from the Garden of Eden. I suspect the American politely smiled while gathering his sample and routinely sent it back home with others he had gathered. But the lab analysis later reported the variety was a rare hard white landrace, so we have been increasing this Amber Eden for the past couple years and bakers praise its quality.

NPR: What are your thoughts about the situation in Ukraine today?

Richard: The news of the war is deeply disturbing and I hope Americans will stand in solidarity with the people of Ukraine for freedom’s cause. During our Revolutionary War notable help came from abroad in terms of material aid as well as the heroic service of foreigners. French commander Marquis de Lafayette and the Prussian general Baron von Steuben stood shoulder to shoulder with General Washington during the years of our struggle for independence. Perhaps lesser known but of special significance was the remarkable service of Polish officer Thaddeus Kosciuszko who helped win victory for the Continentals at the Battle of Saratoga which is considered the turning point of the war. He later returned to Europe and fought against autocratic rule in his native land as well as in Ukraine.

My special interest has been in joining with others to promote the work of A Family for Every Orphan (AFFEO) to provide safe havens for Ukraine’s most vulnerable children. AFFEO also provides food for those in need through its Operation Harvest Hope bakeries in Ukraine. Until the tragic outbreak of the war, no nation on earth had done more to reduce orphanhood than Ukraine through a remarkable collaborative of churches, government child protection agencies, and social service organizations. I hope work continues for these vital efforts in the land that has given so much to provision others throughout the world.